HOME | AUTHOR BIO | EXCERPTS | AUTHOR'S NOTE | HISTORICAL BACKGROUND | CONTACT

Selected Excerpts

A poem by Lalita Gandbhir

from the book's preface

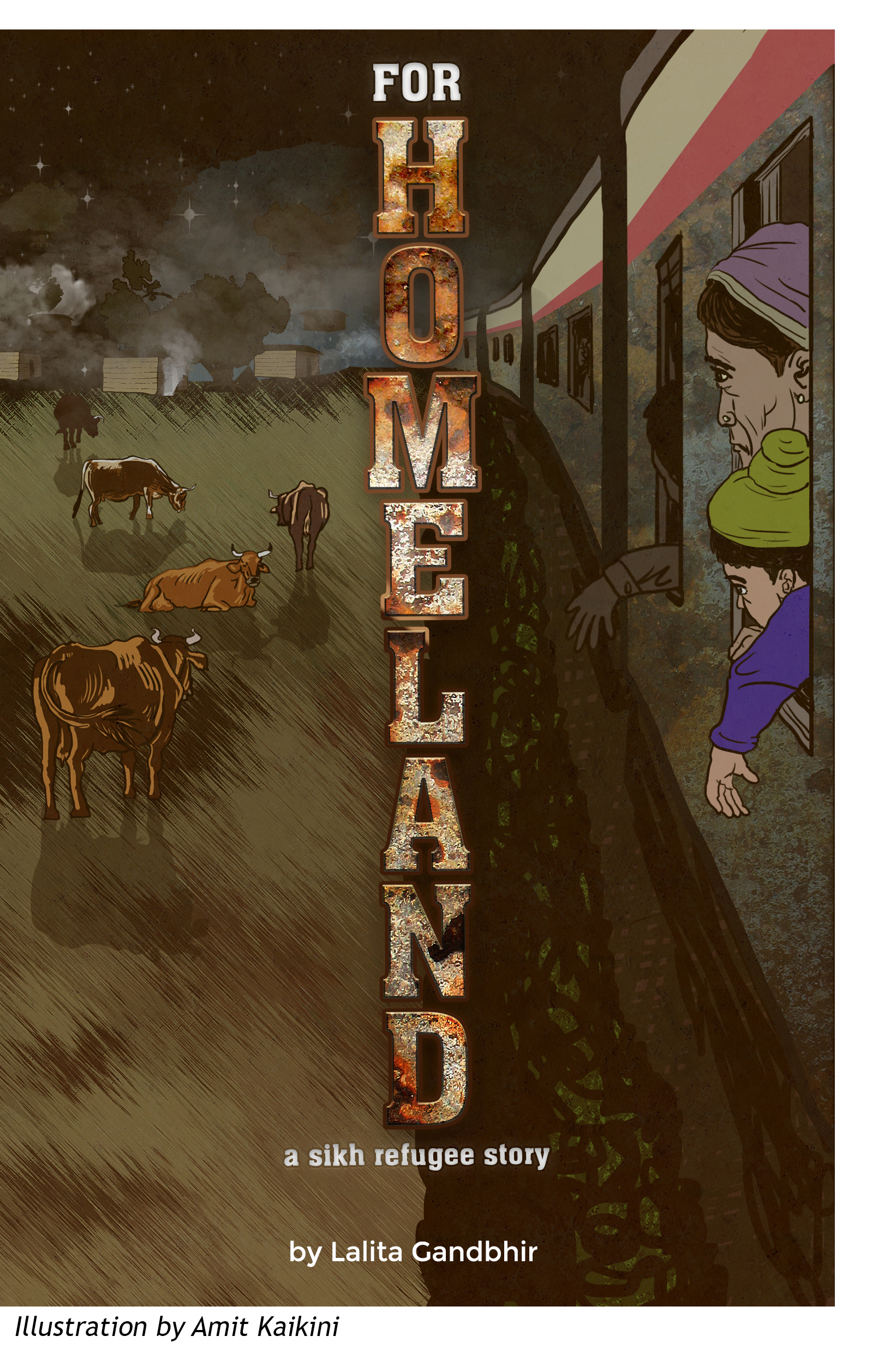

Out of our ancestral homes in the middle of the night

They dragged me, my friends, my neighbors and my relatives

Drove us out of our village,

And chased us through fields and jungles.

I ran.

My feet bled, I stumbled and I fell.

But I got up and ran again because I heard shots.

I didn't have a single moment

To turn and cast one last glance

At my beloved home and village on fire.

They chased us till we were

Out of our country.

In the strange new land

My friends, relatives and neighbors

Started their search for new homes and horizons

And scattered.

Since that time, tormented, alone and lonely

I struggle to find my home, my village and my country.

"The other children say we're refugees and that we're ruining their lives," said Darashan. "They say we're like a contagious disease invading their homes."

"If you ignore them, their words won't hurt you," Bhajan said gently. "Children just parrot what they hear grownups say."

"If our coming here isn't our fault, whose fault is it?"

"I blame the people who forced us out of our home," said Bhajan. "There's no reason we couldn't have kept living in our home, even if it is a Muslim nation now."

"Are the Muslims to blame, then?"

"Only the ones who forced us to leave."

"Where do we live now?"

"In India."

"Will India force us to leave, too?"

"No, it's a nation for everyone."

"But most of the kids here say they're Hindus."

"All of us were Hindus once. Our family is Sikh, but my grandfather was born in a Hindu family."

Darashan was unable to grasp the complexities that Bhajan was trying to explain.

"If we're Sikh, why don't we move to a Sikh country?"

"There is no Sikh country. This is our country now."

"But won't the Hindus force us out?"

"No, Darashan. You don't have to worry about that."

She hugged him again reassuringly, but his eyes were wide.

How could they possibly be safe if they didn't have a country of their own?

The terrace was expansive, with a multicolored tile floor, arranged in a circular pattern. Next to one wall, pieces of fruit had been laid out to dry on cotton sheets.

Rajkumari started to run in circles, following the pattern of the tiles. Darashan was ready to follow her, but then he noticed a girl in the corner, collecting fruits, and he stopped in his tracks.

The girl knelt near one of the sheets, putting dried fruit in a wicker basket. Soft curls of dark brown hair escaped from her pigtails, blowing gently in the evening breeze, framing her delicate face. Thick lashes shaded her eyes. Her red satin dress shimmered in the reflected rays of the setting sun. To Darashan she seemed not of this earth.

The next day, two bullock carts loaded with men carrying sticks and guns visited the village. Accosting a group of teenage boys, they demanded to see the homes of any Brahmins living in the village. "It's Brahmins who are responsible for the murder of our nation's great leader," they said ominously. "They must pay."

Having made note of the homes the boys showed them, the group trundled away in their bullock carts.

Residents of Rala wondered how Brahmins who never set foot outside the village could be responsible for such a deed.

"If they ask rude questions, why do you have to put up with it?" she asked Binnee. "Why can't you be yourself and tell them what you really think?"

Binnee sighed. "Because I'm a girl." Her eyes filled with tears.

"What if the groom is ugly and old?" Rajkumari asked. "Will you refuse to marry him?"

No, I can't. My parents are poor and I'm a burden. They worry about my future all the time. I'll have to marry any groom who will accept me."

What about your brother, Bhagawan? Don't your parents worry about him?"

"No—he's a boy. He'll get proposals, choose his wife and receive a dowry." Binnee paused in her preparations and turned to Rajkuari, "I have advice for you. Fix your own marriage—a love marriage so you won't be humiliated like me." Rajkumari solemnly nodded.

"If a woman doesn't marry," Gurumukh Singh said, "she has to live with a male relative—like her father or brother."

I don't wan't to live with Darashan and his wife. I'll find a flat for myself."

Gurumukh Singh laughed. "Really! I know only one woman who lives by herself. She's not married and is a doctor. She has a hospital where she delivers babies."

Rajkumari was thrilled. Finally, here was a route to independence.

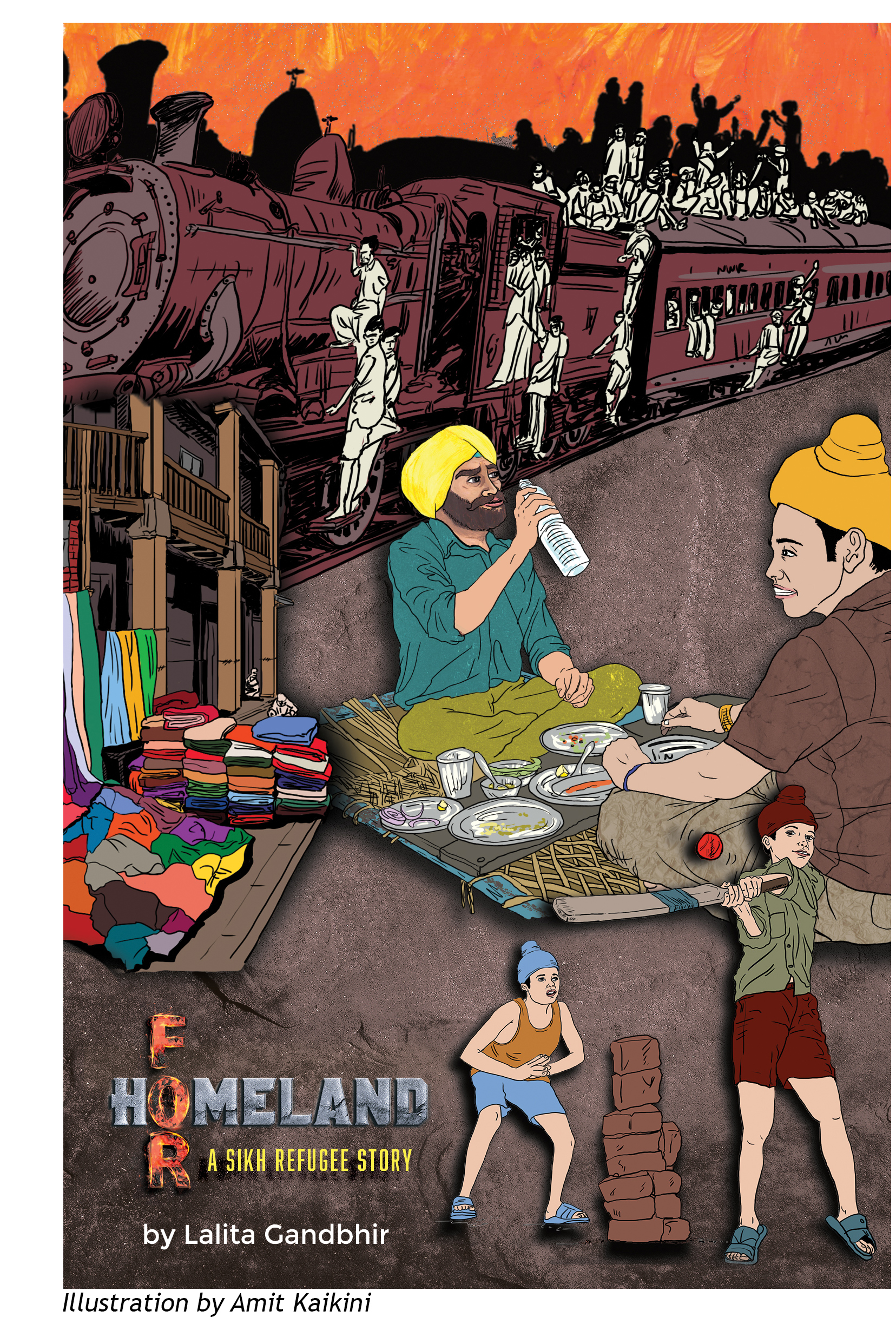

"Murderers!" the mob yelled, and started to hit them with cricket bats and sticks. Darashan grabbed hold of his grandfather, trying to shield him from the angry blows, but the mob pulled him away. A switchblade glinted in the sunlight. As he fell to the ground, he became conscious of a widening pool of blood. Someone was dragging him away from the mob. Then total darkness enveloped him.